A 12-part series to help bolster inner life and mental wellbeing for the Homerton Community, particularly during covid-related isolation: tools, reflections, connections.

Self-isolation can be one of the most demanding things to experience: the rapidity of onset; the way normal life (even the new ‘normal’ of pandemic times) suddenly disappears. Most of the things that keep us stable, define our identities, enable us to live out our plans and responsibilities become difficult or even impossible to access. And this temporary suspension of our experience and self-hood can feel not-so-temporary.

For some of us the demands of isolation on perspective can be profound. Our emotional landscape may feel as though it has shrunk to the compass of our room; or expanded to vast uncharted and unnavigable horizons. You might be feeling many things - anger, frustration, worry, anxiety, boredom, ennui, restlessness, even a secret pleasure in the quiet, or the way that responsibilities can shift and change - or simply feeling nothing, numb or overwhelmed.

Just as there is no one way to be feeling, there is no one way to cope with covid-related isolation. We hope these daily prompts will, however, provide you with a structure to reflect on, build around (and count down) your own days of isolation.

Every day between now and 30th October a Daily Prompt will arrive in your inbox. From later on this week you’ll also be able to access the series via Nexus. We recommend that for now you work through these prompts in order; but that they may usefully be revisited at a later date.

Reflection

Conduct a feelings ‘audit’

Take a few minutes to check in with your emotions. Try to characterise them, and write them down. Now pick one or two, and think about whether you are happy with that feeling, or if there’s something that would make you feel better. That might be by texting a friend for a quick chat; playing a favourite song and dancing around your room; sending an email to your Tutor to say you’re worried about something and want to discuss it. You can’t change all your feelings, but acknowledging them is a good first step. And you might want to come back to this list later and see what’s changed; or what you did to help, or even accept, particular feelings.

Links

From the thoughtful folks at Human Givens - on security & control; intimacy and attention; privacy, meaning, and more

https://www.humangivens.com/human-givens/meeting-emotional-needs-while-combating-coronavirus/

Today’s prompt offers the idea of fortitude, or courage in adversity. Which might also be thought of as stability at some level of ourselves even as things around (and substantial parts of our emotions and experience) are anything but stable.

Fortitude under duress is one thing. Adding long-term uncertainty suggests a different kind of challenge: how long must I be courageous? What do I have to focus my ‘brave’ energy on exactly? How much of this adversity is due to my own perception? When will it end?

Uncertainty is a natural part of our impermanent, unpredictable existence. It is also a defining part of pandemic conditions, even as the certainty of day-in day-out isolation unfolds. Equally, a desire for certainty is a powerful human drive. We live in a risk culture, as Ulrich Beck puts it, where micro-assessments of risk and a strong fascination with the future drive daily life. One might consider fortitude then, as a necessary condition for living with this dance of tension - the fascination with the future (will things be ok) and the very unpredictability around the object of that fascination.

So, we might think of approaching this dilemma in two ways: the first is confidence. That although this particular situation (covid-isolation) is unprecedented, you probably have tools and ways of thinking that mean you can make strong decisions even in the face of not-knowing (reason, analysis, risk-assessment, systems of safeguarding, safety and care around you, emotional depth, relationships, self-regulation, compassion, awareness).

The second is accessing the stable, calm, wise aspects of yourself, aspects that are sometimes swamped by the drama of our thoughts and actions. Buddhist teachings often refer to the trio of ‘stable body, stable mind, stable emotions’. It doesn’t mean that one part of that trio can’t be ill, or suffering, or even unstable at times. What it suggests is that relative stability and strength - fortitude - can be found even in tiny and irregular ways. And one way of finding that fortitude - especially when we are under duress - is being more attentive to the relationship between our body (say, the breath), our thoughts (that confidence around, say, tools and approaches) and our emotions. This attentiveness can help build our habits of daily courage, and stability, so that in moments of intensity we have deep sources from which to draw.

Reflection

Find a comfortable place to sit and, if you feel comfortable to do so, close your eyes. Focus on breathing in, breathing out. Allow your shoulders to move away from your ears and your body to soften.

Now focus on being present in this moment, rather than worrying about what is (or is not) going to happen next. Try staying with this for a minute or two. And if your mind wanders (and its nature is to wander so it probably will) gently bring your attention back to your breath.

Now remember times you have dealt with difficult uncertainty in the past, even a situation that might not have seemed significant at the time. Remind yourself that you have been through this sort of challenge before. You might want to think about what you did, how you responded, what helped you, how you felt when the challenge was over. You can affirm your own courage in the past and draw on that in the here and now.

If you like, write or draw or record a response to this recollection and this process.

Links

https://www.annamathur.com/podcast/ - Episode 01: Dealing with uncertainty

Margaret Heffernan. 'Introduction’. UnCharted: How to Map the Future Together. Simon and Schuster. 2020 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=HK6cDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT4&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false

It’s a truism that change is a constant and necessary attribute of being alive. But knowing that doesn’t always make living in change - especially fast, unsettling, or grief-inducing change - straightforward or indeed manageable. From myth to stage theory (one might say both psychological and dramatic) people have worked hard to find adequate narratives for reconciling themselves to change and to understand how we adapt to it.

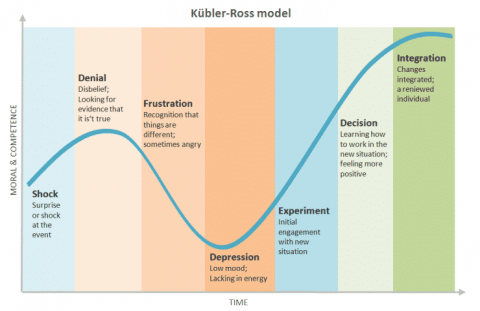

The ‘Change Curve’ is one such narrative.

The curve initially came out of work in the 1960s on grief, led by psychiatrist Elizabeth Kubler-Ross. It’s been applied since to coaching, personal development and (not always kindly) to organisational change particularly around ‘restructuring’. It’s also quite specific to cultural types and norms (ideals of selfhood, for example, in the mid-twentieth-century US). And as a model for understanding grieving it can be read as unhelpfully prescriptive. Pandemic conditions have offered a mild restoration of the model, however, as a tool for thinking more deeply about the inner stages we might go through during intense change. It mostly applies to changes foisted upon us (a pandemic) but can also model changes we seek out intentionally (starting a challenging new project; greater psychological attentiveness).

One particular insight with this model - stage theory, really - is that it’s possible to be at different points in the change curve at the same time and on the same issue. So professionally one might be at the Decision end of things whilst inwardly feeling very much in the midst of Frustration or Depression. Like most things its just a tool, but potentially helpful in exploring more deeply how our cognitive and affective processes combine to determine both felt reactions and perceptions.

Reflection

Where do you feel you are on the Change curve?

Think of a particular situation - being in isolation, beginning something new, a project - and ask yourself, ‘where am I on the curve with this particular thing’? Are there signs of movement along the curve? Can you identify particular thoughts, experiences, emotions that hint at, or express, points on the curve?

Links

David Wilkinson ‘Is the Change Curve a myth?’ https://www.oxford-review.com/is-the-change-curve-real/

Poems of Anxiety and Uncertainty. The Poetry Foundation

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/collections/101584/poems-of-anxiety-and-uncertainty

Keeping a record of our experiences - for ourselves, or for others - can be seen as a quintessentially human activity. Whether in the form of diaries or letters, account books or chronicles, and expressed through acts of painting, carving, writing, or typing, such records bear witness to moments of personal and social history. Writings and images can speak from the past, and speak to the future; but can also help us make sense of the present.

[Letter from Homerton College Archive - a student writes home in 1918.]

In moments of stress and crisis, we might find ourselves turning or returning to particular forms of writing. Childhood favourites can provide comforting familiarity; sacred texts can offer opportunities for lament or affirmation. Writing can provide escape, can transport us to fantastical realms, to distant pasts, or inside other people’s lived experiences. Or (as now), it can help us work through an all-too-altered reality.

The writing of pandemic diaries has been used across the globe to witness events, to register change, and to provide personal solace and reflection. Committing to a daily ritual to capture our experiences in words, images, or sounds, is a powerful way to inhabit the present moment, and to reconcile ourselves to our changed quotidian environments. Journalling can become an important part of a self-care routine, granting us permission to express emotions, articulate concerns. Keeping a diary, then, is a way of marking time, of taking time for yourself, and of making a record of your most human experiences for other times.

Reflection

How are you keeping a record of your experiences of covid-isolation? Take time today to notice and note down the details of your daily life. What have been the telling moments, or repeated patterns? If you have already been diarising your time in isolation, try a different way of keeping a record of today: take a photo, write a haiku, make a recording. Begin to collect and consider your responses to these prompts as part of a daily journal to chronicle your isolation days.

Links

Journalling as an act of self-care:

https://www.annafreud.org/on-my-mind/self-care/writing-things-down/

The Quarantine Diaries from the New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/30/style/coronavirus-diaries-social-history.html

Quietude. Stillness. Calm. Peace.

The practice of self-isolation has not always carried its current distressing and negative connotations. For some people the deliberate withdrawal from every-day life, for short or extended periods, is central to an inner life of stillness. From the medieval anchoress to contemporary retreats or even time alone in a forest, forms of withdrawal are encouraged in many of the contemplative traditions. And the stillness that both characterises these drawing-away-froms and is made possible by them is seen to be fundamental to a capacious inner life.

Quietude - or inner stillness - suggests a capacity within ourself to quell the tumultuous thoughts, to replenish, to be able to look inwardly and outwardly with interest, intelligence and compassion because we are part of things greater than ourselves. Equally, because we are more fully ourselves. And so can to some degree look upon ourselves and the world with equanimity. It’s concomitant with rest, relaxation, respite, breathing space. And a frank appraisal of realities.

For most of us withdrawal is more of an on-occasion, sometimes state rather than a desirable permanent state. But the quietude it cultivates has a residue. As professional wanderer and writer Pico Iyer puts it: ‘in an age of acceleration, nothing can be more exhilarating than going slow. And in an age of distraction, nothing is so luxurious as paying attention. And in an age of constant movement, nothing is so urgent as sitting still.’ ( The Art of Stillness, 2014). That might mean time without external stimulation; or time not dedicated to achieving something (even relaxation); or being somewhere quiet that restores us.

This on-occasion stillness clarifies our senses; reminds us of priorities; energises us for the next set of demands and encounters with the world; increases our insight and compassion. But it goes beyond this. It reminds us that there is more to life than ourselves. It increases capacity for, as Iyer says, giving blessing rather than only our distraction, exhaustion or preoccupation. You could say it is a necessary condition for wisdom - that organising virtue that helps us decide when to act and when to refrain, when to exert and when to accept, when to celebrate and when to grieve...

Rather like the regular digital-detox popularised by many working in tech, a change of distraction, and an intentional change of attention, can also change us.

Reflection

Try taking a break from digital distraction - social media, streaming, internet searching - even for an hour or two. More if you want. You could do this for just one day. Or maybe a set time every day: say 30 minutes every evening Mon-Fri. You could approach this respite with some intentions (to read, or meditate, or play music…) or with none. And you might allow whatever feelings emerge to surface - excitement, boredom, worry - with the idea that you’ll acknowledge them with compassion. You might remind yourself to be gently curious about how you feel and think afterwards.

Links

https://www.ted.com/talks/pico_iyer_the_art_of_stillness/transcript?language=en

The works of Thomas Merton, Thich Nhat Hanh and Julian of Norwich offer useful introductions to practices of quietude from various contemplative traditions.

We are all living in strange and challenging times. One aspect of recent life that has been most strange - and most challenging - has been time itself. We may feel that someone else has taken control of our temporal references, and interrupted the regular rhythms of life. Days stutter and sprint away, seemingly stuck in groundhog loops, or swiftly Zooming by (quite literally).

Marking time - as these email prompts have done - has taken on new significance, as we count down the days left of isolation, or project epidemiological curves into future weeks and months that have yet to happen. Many of us have been more conscious than ever of the passage of time in our surrounding environment, sequences of leaf-bud-bloom-fruit-foliage captured squarely on social media profiles. Alongside these perennial natural cycles, our individual experiences and collective cultures of time (philosophical, mathematical, embodied, emotional…) can be reaffirmed or redressed.

Researchers into the history, psychology, and sociology of time have often identified an accelerated temporal modernity aligned with an online, capitalist society. They have argued that we need to consider the socio-technological assemblages of contemporary life as mutually-constitutive experiences that can render us supposedly ‘time poor’, harassed by the very devices that were supposed to help us save and pace our time. However, such temporal pressures, they argue, are disproportionately felt by some members of society - within these wider cultural contexts, we can individually live in time very differently.

The rush to keep up, or to outpace, can feel particularly acute given the time pressures of the 8-week Cambridge term. We may, then, see a period of self-isolation as an opportunity for enforced deceleration - for a turning away from the need for rapid action, towards more meditative and drawn-out work. Following scholars of boredom, we might identify a slowing of the pace of life not as as lack or a denial, but as an attentiveness; a deliberate recalibration and reconnection to what we value and hold dear - to what we want to spend our time on, and who we want to spend our time with.

However you are marking this strange and challenging time - remember, it will pass.

Reflection

Take a few minutes to reflect on how you have been marking time - and, in particular, where you have felt yourself making adjustments to the haste and pace at which you have been living. Try to imagine yourself deliberately inhabiting a slower pace of life, even for a short amount of time, and how that might feel. How might you bring some of that feeling into your more usual hurried life? Consider choosing one activity (reading a short story; making a cup of tea; writing to a friend) and doing this slowly and deliberately.

Links

On boredom: https://www.idler.co.uk/article/book-of-the-week-life-a-users-manual/

Gillan Beer on the ‘rumpled and energetic’ forms of mathematical time in Alice: https://www.nature.com/articles/479038a

The Experience and Perception of Time: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/time-experience/

A recent review essay of current scholarship on science, society, time and modernity: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0162243919845140

---Content Warning: today's prompt discusses bereavement, loss, and mourning---

Today of all days writing about grief is difficult, immediate, and very real. One thing pandemic living makes it hard to escape from is loss. The loss of our everyday. The absence of rituals and spaces. The loss of experiences and parts of our self-identities. The loss of our health, temporarily or otherwise. The loss of people we know and of people we deeply love. Even a sense of loss for people and things we’ve never known of until now.

Our mourning can be intense and personal; or exist as a vague sense of malaise and discomfort. It can take the form of heightened anxiety, anger, depression, or even plain old tears. It can be ever-present, or flit over us, around us, for no apparent reason. There are unpredictable potential losses too - what else might I lose, when might I have to mourn, will people I love be alright? This sense of pending but un-pin-down-able loss is sometimes called anticipatory grief. And if our sense of loss doesn’t hold the promise of resolution this ambiguity can seem overwhelming.

Pandemic conditions make living with loss harder than normal. Daily living throws it into our vision. Even these daily prompts might be uncomfortable reminders of realities. So, what can we do with all of this?

At heart mourning is both an attempt to render our experience approachable, and simultaneously to change the nature of the things we are seeing. It’s a natural, universal response even as its expressions are particular, specific and profound. It is our deeply felt, deeply experienced pain-borne response. Equally, we are driven to evade it, to avoid the loss and to do all we can to prevent it happening in the first place. At the right time though (eventually, but perhaps also immediately) grief can be an opportunity to see things more clearly: the things we value, the preciousness of the present, the meaning in the quotidian, our loves...

Our personal pains can sometimes also connect to global pains (a connection that is both burden and insight, perhaps, of our time and education). For many people the pandemic has exacerbated a sense of political mourning, making more visible the '"induced conditions of unlivability", which are the living legacies of racism, nationalism, sexism, exploitation, and other structures of institutionalized or ritualized abuse and disregard.’ (David McIvor et al, ‘Mourning Work: Death and Democracy During a Pandemic’ 2020). We see things now in a a different way. And sometimes this can lead us to greater insight about what we care about. For ‘mourning clarifies our attachments and practical commitments’ and can ‘inspire a re-evaluation of life and a means of ... self-critique and self-scrutiny...’ (McIvor et al). In other words, it can move us towards a life of greater insight and greater compassion; a refined self-hood and refined love. But it’s also terribly painful. And so we acknowledge our grief, even as we gently become a more clarified version of ourselves and remind ourselves of what and who we really love.

Reflection

Headspace’s 10-minute guided meditation on grief can be useful if you want to sit quietly with your feelings, even the unnameable ones - on life, a particular loss, grief...

Links

'Coronavirus Grief’ The Mayo Clinic

Stephanie O’Neill. ‘Coronavirus has upended our world: it’s ok to grieve.’ NPR Shots. 26 March 2020

We began these prompts with an acknowledgement of the altered emotional landscapes of pandemic times. We can be feeling too much, too little, too often. From what had been relatively tranquil terrain, we may feel thrust into a turbulent emotional existence, beset by eruptions, floods, or the silence that sits at the eye of a storm. One way to anchor ourselves within such a mutable inner world is to chart the specific contours of this landscape - in other words, to identify and become aware of specific emotions.

We know that how we name our emotions is determined by our time and place, and our language, as well as our ability to articulate what it is we are feeling, and the legitimacy those feelings are granted. We now speak in a vocabulary of the expression of the emotions rather than one of sentiments, passions, or affections. When communicating in English we might borrow terms from other languages to capture certain nuances of feeling. To elicit that frisson of insightful understanding; a comforting hygge of empathic experience; or a saudade for something impossible to have. Indeed, the widespread sense of being ‘bored, listless, afraid and uncertain’ (Zecher) during pandemic days has been characterised as an archaic emotion itself - acedia.

An enhanced and open emotional vocabulary is an important first step to recognising and realising how our feelings relate to other aspects of our living beings - such as how we hold ourselves in physical space, or how we make decisions. Assertions of the opposition or separation of the rational mind from the emoting self are increasingly seen as unhelpful and outdated dualisms. Rather than emphasising the necessity of controlling or conquering our emotions, fields from innovative leadership practice to early years education to cultural history are developing more sophisticated ways of working with and contextualising emotional awareness.

But what does this mean in practice? Perhaps we can say that having additional insight into our own interconnected self can ensure we pay appropriate attention to our physical, mental, and emotional health. We can consider how, when, and why we give voice or give vent to our own state of mind. We can become aware of the processes by which we convert internal feelings into external emotions, and then to consequent actions and reactions (or even inaction).

What has been called our ‘emotional intelligence’ is in part, then, that self-knowledge of the relationships between how we are motivated to take certain choices, respond in certain ways, or feel able to change or regulate certain practices rather than others. We can trace out potential shifts in our patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours - and even begin to change them.

Such reflective work also engenders empathy: acknowledging and working through our own emotions helps us appreciate the experiences of other people. We can imagine how others are feeling; pay attention to what others may be expressing; and communicate with others in a frank and specific way how we are feeling. In this time of public health crisis, when communal and collective understanding and action is so crucial, such emotional literacy and empathy is perhaps more important than ever. By charting our own landscapes within, we can begin to address the wider landscape beyond.

Reflection

Give yourself 5 minutes to write down as many different emotions as you can think of, in any languages you prefer. Now pick any two of these emotions. What would it take (whether thoughts or actions) to move from one emotional state to the other? If it seems difficult to determine how you might manage this yourself, consider what you would advise someone else to do.

Take a few moments to reflect on this exercise - were you surprised by how many emotions you could name? What challenges could you see in trying to move from one way of feeling to another? How did certain emotions connect to certain thoughts, behaviours, or decisions?

Links

More on the importance of ‘reviving the language of acedia’, by Jonathan Zecher: https://historiesofemotion.com/2020/09/08/acedia/

‘The Emotional Contagion: Feelings, Emotions, and the Pandemic. An interview with Tiffany Watt Smith’:https://emotionsblog.history.qmul.ac.uk/2020/06/the-emotional-contagion-feelings-emotions-and-the-pandemic-an-interview-with-tiffany-watt-smith/

‘Strategies to Manage Pandemic Emotions’, from Christa Santangelo:https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/hope-and-empowerment/202007/strategies-manage-pandemic-emotions

Sometimes it’s hard not to feel like a fraud. Questions intrude on your mind when comparing yourself to others around you. Has there been a mistake? How am I getting away with this? Why can’t I cope while everyone else is? Why aren’t I as confident as other people seem to be?

Even though you have every right to claim some understanding of a situation, authority in some part of a subject, or entitlement to be in the room - you feel you don’t. And worse, everyone else can tell you’re a fraud. That you’re where you are and doing what you’re doing because of luck rather than effort. The voices of doubt can also be triggered by external judgements - the more others around you ascribe qualities to you, tell you how clever, amazing, kind, brave, energetic, happy (etc.) you are, the less you believe them.

The idea that we are ‘faking it’ is ancient, but it has more recently been called imposterism, or imposter syndrome. Many high-achieving people, at any stage or age, confess to such inner doubts and anxieties, and the attendant lack of confidence, perfectionism, or self-sabotage. And we know imposter syndrome can disproportionately affect some groups who already bear the weight of discrimination and inequality.

The tricky thing is that imposterism is rarely entirely true or false. Most of us are where we are and doing what we’re doing for a complex set of reasons - hard work, the support of key people, energy, aptitude, courage, and sometimes a bit of luck. And most of us have moments of, say, high joy and energy with friends, only to collapse with exhaustion as soon as we’re by ourselves. From the outside it can be difficult to tell how others are coping.

Scholars have argued that calling imposter syndrome a ‘syndrome’ - denoting a collection of symptoms or behaviours that require a cure - is itself a sign of a culture obsessed with achievement and hyper-classification. And that this naming is deeply connected to the histories of twentieth-century psychology and organisational studies, amongst many disciplines, as well as the almost unquestioned idea that our selfhood is endlessly improvable and malleable, and entirely up to us.

Like many things, then, acknowledging the rearing head of ‘imposterism’ is about proportion and context (luck may have played a part in me being where I am now, but so did x and y qualities, this breakthrough, this hard work, these people). The added stress of pandemic times can make this mental work harder, converting what might be quite usual feelings of inadequacy into full-blown doubt. We may be isolated from our usual supportive communities, finding it difficult to contribute to online conversations, or sense that whatever we do is not enough. And those questioning voices within ourselves can shout louder in the hush of self-isolation. However, such doubts can, in fact, be productive. They can help us to question, to strive, to achieve. If we can work to acknowledge, accept - and even to share - our fears and struggles we can begin to take small steps to live with them, to move beyond them, and to remember that to wrestle with self-doubt is human.

Reflection

Think about how much you’ve achieved in the last 2 years. How far you’ve come. You can be quite specific with this - what you’ve overcome; what you know now that you didn’t then; what you’ve done; what you’re proud of. These things don’t necessarily need to be about work or study - think about all aspects of your life. It can help to list these things somewhere that you can look at later during moments of doubt.

Conversely, imagine what it would be like if you saw yourself - as you are now - as sufficient. With things to learn, and qualities to cultivate, and faults and messiness, yes, but as a person sufficient. Enough. Adequate. What would that feel like? If you were enoughwhat would you do? If the thing you think is limiting you or is an irredeemable lack turns out not to be limiting, or not true, what would that enable you to feel? To envisage? To do?

Links

Katherine Calflisch. ‘Imposter Syndrome: The Truth About Feeling like a Fake’. American Society of Microbiology 14 Aug 2020

Dana Simmons ‘Imposter Syndrome: A Reparative History.’ Engaging Science, Technology, and Society (2) 2016, 106-127https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b5f7/7c27056255931758ea9c0b1caef83e8e901b.pdf

https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/overcoming-impostor-syndrome.htm

Many of these daily prompts have been a call to live deliberately. An opportunity to step back from the immediacy of instinctual reaction, into a more reflective mode. Such critical attention can usefully be paid to ourselves, and our immediate environments; but what if we turn that gaze to our social, emotional, and political moment? What is at stake on a wider stage? Over the past eight months we have all witnessed how interconnected our own experiences are, but also how powerful individual resolutions and actions may be. We may have been surprised to discover what is of most importance and value to us. We have, perhaps, determined that there may be an opportunity to forge more sustainable, more equitable, and more rewarding ways of living, learning, and working. A post-pandemic world may, then, provide us with an opportunity to set renewed intentions, and to build back better. We can determine what kind of post-pandemic world we want to live in; and consider how our actions can bring that world into being.

If you decide you want to change the world, you will not be alone. IPSOS recently surveyed more than 21,000 adults from 27 countries on their hopes for a post-Covid world. They found that ‘72% would prefer their life to change significantly rather than go back to how it was before the COVID-19 crisis started. Further, 86% would prefer to see the world change significantly – and become more sustainable and equitable – rather than revert to the status quo ante.’ (Nicholas Boyon on the IPSOS Global Survey, ‘How much is the world yearning for change after the COVID-19 Crisis?’)

From this, and other studies, it is clear that many many people want their worlds to change. But converting that hope into real-world developments requires individual and collaborative action. There will be no one way of answering the urgent questions raised by our pandemic moment; no single response will suffice. Rather, as Perspectiva Founders Tomas Björkman and Jonathan Rawson have suggested, ‘a story of stories’ will provide ‘the renewal of hope for our world’.

Today, then, think about how your own experiences, story, and intentions can contribute to shaping our collective future.

Reflection

Take ten minutes to write a letter to your future self, capturing what you are most hopeful for in a post-Covid world. What aspects of life have you come to value more? What would you like to change? What causes could you better champion? By setting these intentions, what actions can you take now to begin to bring that world into being? Think about what you might be able to achieve in different timeframes - if you were writing to yourself a year from now; or 5 years from now.

Links

‘How much is the world yearning for change after the COVID-19 Crisis?’. IPSOS Global Survey for the World Economic Forum (Aug/Sep 2020) https://www.ipsos.com/sites/nexus.homerton.cam.ac.uk/files/ct/news/documents/2020-09/global-yearning-for-change-after-the-covid-19-crisis-2020-09-ipsos.pdf

Nicholas Boyon, Summary of the IPSOS Global Survey for the World Economic Forum, IPSOS, Sep 2020

https://www.ipsos.com/en/global-survey-unveils-profound-desire-change-rather-return-how-life-and-world-were-covid-19

Poems of Hope and Resilience. The Poetry Foundation

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/collections/142028/poems-of-hope-and-resilience

Some prompts for thinking ‘post-Covid’

Jonathan Rawson. ‘Bildung in the 21st Century:Why Sustainable Prosperity depends upon reimagining Education’ Centre for Thinking about Sustainable Prosperity Essay Series, No 9. June 2019 https://www.cusp.ac.uk/themes/m/essay-m1-9/#1475182667098-0328ae0f-4bcbf2c7-159efa7b-6ee7573a-4c7b

OECD. ‘Building Back Better: A Sustainable, Resilient Recovery After COVID-19’. 5 June 2020 https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/building-back-better-a-sustainable-resilient-recovery-after-covid-19-52b869f5/

Perspectiva

https://www.systems-souls-society.com

Unalloyed joy! O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!

Or maybe…. meh. Or worry. Or worry that you’re insufficiently joyous...

It’s not the sort of thing most of us have had to think about much. But the realities of adjusting from isolation - or even lockdown - to a different mode of living are complex. For some of us the enforced quiet and the strictures of isolation can be comforting, even pleasurable: a slower pace, an irrefutable reason for saying no to things, that permission to watch every Netflix thing. Others of us can’t wait - just cannot wait - for freedom and other people and encounters. And we feel impatient. It’s even possible to criticize ourselves for not having a better isolation; or for failing to maximise the experience, or for not having a firm to-do list the moment we’re allowed out. And although we know and perhaps also hope that life won’t be exactly how it was before Covid, the lure of ‘returning to normal’ hints at our desires for familiarity and the fulsome capacity to live out our expectations.

People who’ve spent extended time in isolation - on retreat, being ill, for fieldwork- speak of the long and sometimes jarring return to a life that is often much noisier, crowded, changeable, and weirdly demanding. Antarctic expedition leader Rachel Robertson writes that in all of the epic preparations she and her team made for 9 months living in close quarters in -35C degree temperatures, the one thing they hadn’t prepared for was coming back home. The noises, the crowds, the sensory overload. Being touched. The speed. The array of choice suddenly available. Even the smells.

And even though two weeks isolation isn’t quite the same as nine months in Antarctica one could make the case that cognitive adjustments required to move from any extreme to a significantly less extreme are similar. For the intensity of one’s thought-life and self-determination has to change. The pattern of days and hours, which can quickly become comforting, can’t continue in quite the same ways. The closely felt and observed things that limit behaviour - from walls to rules essential for survival - are suddenly altered. There are so many things we’ve longed to do that are now suddenly possible.

Paying attention to this experience of transition, then, helps us to understand more about why we are responding, deciding, acting or feeling the way we are. And this knowledge can bolster our inner resources for the next time. Not necessarily making it easier, but perhaps less fraught. Right now (November 2020) another lockdown has just been announced. We exit one challenge and find ourselves squarely in another situation that for most of us is unprecedented, uncertain and not-ideal.

With callooh callay in mind may there be joy in the daily freedoms, and even in the constraints.

Reflection

Spend a few moments thinking about how you felt (or how you think you might feel) on ‘release day’. What are you looking forward to doing most of all? To experiencing? Ask yourself why. Ask why those things matter to you. And when you’ve answered that, ask why again.

Links

Rachel Robertson. Emerging From Isolation: 7 Tips from an Antarctic Expedition Leader. Financial Advisor. 25 June 2020

https://www.fa-mag.com/news/emerging-from-isolation--7-tips-from-antarctic-expedition-leader-56544.html

6 Tips for Returning Home after a Silent Retreat

https://www.eomega.org/article/6-tips-for-returning-home-after-a-silent-retreat

David Farrier ‘With Apologies to Susan Sontag: We’re Going to Need Metaphor to Get Through this Global Illness’. Literary Hub 15 May 2020

https://lithub.com/with-apologies-to-susan-sontag-were-going-to-need-metaphor-to-get-through-this-global-illness/

‘...how astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed…’ (Virginia Woolf, ‘On Being Ill’ 1926)

These Daily Prompts have been encouraging us to bring greater attention to our experience, expectations and perspectives during COVID-related isolation. This approach has assumed that curiosity about these things helps build our epistemic poise and inner fortitude (it also assumes that these are good things). And it’s predicated on the idea that some forms of vital knowledge can only be accessed from within an experience: that the time to pay attention is in the middle of it all, and just afterwards.

Equally, we are not exactly reliable narrators about our experience: we’re liable to forget or fold multiple moments into a single memory. And we tend to craft memories - and so also our decision-making for next time - from the tail end of experiences: to put it bluntly ‘our brain values the final few moments of the experience more highly than the rest of it’ (Cambridge neuroscientist, Dr Martin Vestergaard 21 Oct 2020).

Focused recollection, then, with some kind of record - whether text, sound or image - can help us see ourselves later when our memories cannot quite. It is a tool for more accurate renderings of our lived experience. It can also help us ask better questions. Virginia Woolf’s 1926 Essay ‘On Being Ill’ begins ‘...how common illness is, how tremendous the spiritual change that it brings, how astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed...what ancient and obdurate oaks are uprooted in us in the act of sickness…’. Isolation might not be an illness (although it might well be) but it does often uproot the trees of our regular life.

So this prompt asks what would happen if you could remember some of the country made newly visible to you by the experience of isolation and pandemic. What if you could recall not only the general landscape of this country - its temperatures and colours and rough location - but its textures, its smells, the details of light and shade and your apprehension of those things? Its water and plants and lakes and valleys? What if you could hold on to the things you’re seeing?

And what do you hope you can carry with you, onwards? Perhaps it’s a greater sense of thankfulness for relative freedom of action and movement. Maybe it’s the simplicity - of not having to make complex decisions about plans or clothes or arrangements. Or the quiet. Perhaps equally it’s the complexity of juggling multiple commitments, friendships and projects, all from your laptop or phone. Or having a deeper level of relationship with people close to you and relishing that. Or more time for yoga. As one contributor to the ‘Solitude: Past and Present’ blog put it, lockdown helped them live ‘a more considered life’. And this was something they really wanted to keep on doing.

So, what do you want to keep on doing? How do you wish to live? With a greater sense of stillness? Or attentiveness? Or of aliveness? More broadly, what is this experience exactly? We’re the first humans to live in a pandemic of this scale with the capacity for global connectivity: self-isolation whilst potentially connected to thousands. What is in this we must realise and actualise? What is there we can learn? What do you wish to do with this knowledge?

Reflection

An exercise in naming the parts: try listing some aspects of the experience you want to keep, or those elements of your previously undiscovered country that stay with you. The act of naming can be a powerful tool for both recollection and shift in perspective. So aim to be as precise as you can, particularly naming feelings, ambitions, reaction. Equally, you might reflect on those parts of isolation that were difficult, detestable,tedious, confronting - using the same guide to precision as above.

Links

From the Solitude: Past and Present project at Queen Mary, University of London

https://solitudes.qmul.ac.uk/blog/the-unexpected-solace-of-lockdown/

Christopher Germer ‘To recover from failure, try some self-compassion’. Harvard Business Review, 5 January 2017

https://hbr.org/2017/01/to-recover-from-failure-try-some-self-compassion?ab=at_articlepage_relatedarticles_horizontal_slot3

‘Study reveals brain mechanisms underlying irrational decision-making’. Cambridge Neuroscience News, 21 Oct 2020

https://www.neuroscience.cam.ac.uk/news/article.php?permalink=5ff4d0f26d

Virginia Woolf. ‘On Being Ill’ (1926)

http://www.woolfonline.com/?node=content/contextual/transcriptions&project=1&parent=56&taxa=45&content=6225&pos=13

Additional daily prompts:. https://10daysofhappiness.org/